The Sherlock Holmes stories published under the purported authorship of Conan Doyle provide frequent (and often contradictory) descriptions of the rooms at 221B Baker Street rented by Holmes and Watson. No story ever directly mentions either a bathtub or a water closet (toilet).

In The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax, Holmes deduces that Watson has enjoyed the Turkish baths and asks him,“Why the relaxing and expensive Turkish rather than the invigorating home-made article?” In The Sign of the Four, Watson returns to Baker Street after a long day of sleuthing and Watson was,“limp and weary, befogged in mind and fatigued in body.” But then Watson writes,”[a] bath at Baker Street and a complete change freshened me up wonderfully. When I came down to our room I found the breakfast laid and Holmes pouring out the coffee.” This passage makes clear that Watson’s bedroom was upstairs from the sitting room and states the obvious, that the renters were able to take a bath in their lodgings.

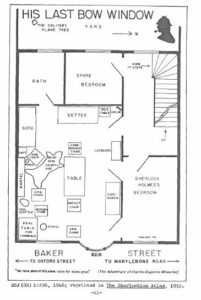

Julian Wolff, in 1946, suggested a layout of the Baker Street flat that included a bathroom opening off the sitting room on the first floor (American second floor). No passage in the Canon supports a bathroom on the first floor, although the above quote from The Sign of the Four would indicate that there was a bath available to Watson on the second floor above the sitting room.

William Baring-Gould in a 1967 article in The Baker Street Journal suggested three possible ways for Watson to take such a bath:

1. A small room converted for use as a bathroom with a tub and standing hot water heated by the kitchen fire. The tub would usually have been metal with a wooden rim.

2. A hip bath with a high back, made of metal that was short so that the legs hung out of the tub. Hot water was supplied by a servant who carried it up from the kitchen or less commonly by a hot water system heated by the kitchen stove in the basement.

3. A flat shallow pan of metal painted to look like wood that could be stored under the bed. When in use, the tub was set before the fire with towels underneath to protect the carpet. The tub was filled with hot water brought up from the kitchen (two floors below) in metal cans or by a hot water system described above.

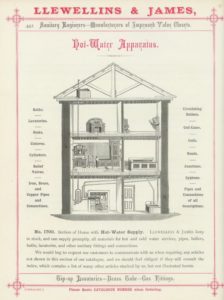

By 1880, many English homes had hot water systems warmed by a separate boiler behind the stove in the basement kitchen with pipes that carried the water throughout the house. By the 1880’s, the cylinder system had appeared as a safer and more efficient alternative to a hot water tank on the roof of a house. A hot water storage cylinder was placed just slightly above the range in the kitchen. The hot water was drawn off from the expansion pipe that extended upwards from the top of the cylinder to above the cold-water tank so there was no risk of the system being inadvertently emptied.

No story in the Canon provides any hint that the residents of 221B ever defecated or urinated, although we may deduce that they did so. Flush toilets were known as “water closets” in Victorian Britain and involved a water reservoir on the wall above the bowl were the user sat. The pull of a handle suspended by a chain from the water closet released water which flushed the waste in the bowl down into the sewer system. By the early 1870’s, water-closets were commonly provided in London housing. Crapper & Co. was perhaps the most well known water-closet manufacturer at the time.

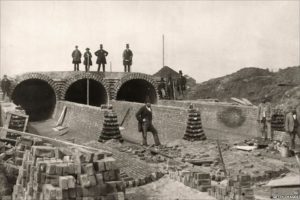

221B Baker Street likely had running water throughout supplied by a cistern on the roof, which was in turn connected to a water supply that ran a few hours a day. Victorian London was served by eight water companies, which before 1870, only provided intermittent water service for a few hours a day to rate payers. Each house had a water cistern in the attic or on the roof which was filled each day when water flowed for a few hours. After 1870, a system of constant water supply began to be introduced to London, although it took over 20 years and a huge amount of pipe retrofitting to bring the “constant” to all of London. The West Middlesex Water Company supplied water to the Northwest section of London, including Marylebone (and thus Baker Street). By 1891, 43 percent of the houses supplied by this company were on constant. The change to the constant system involved the water company reworking its water main system under the street to each house and it required each homeowner to redo almost all of the piping system inside the house. The constant water system involved a much higher pressure of water, which the older pipers connected to a cistern could not handle. New fittings and faucets were also required inside the home when the conversion was made.

Thus, by the time that Holmes and Watson rented their rooms on Baker Street from Mrs. Hudson in January 1881, they almost surely had access to piped, running water and to a water closet in the building. More than likely, a room had been converted to a bathroom by the time they rented, but the “constant” water supply was probably introduced to Baker Street later during their tenancy. The Canon suggests there was a bathroom on the second floor of 221B. The precise location of the water closet(s) is not known.

Sources:

Baring-Gould, “Mrs. Hudson’s Inheritance”, Baker Street Journal, Vol. 17 (March 1967): 28-36.

Hardy, “Parish Pump to Private Pipes: London’s Water Supply in the Nineteenth Century,” Medical History, Supp. No. 11, 1991: 76-93.

Wolff, “I Have My Eye on a Suite in Baker Street,” Baker Street Journal, Vo1. 1 -old series (July 1946): 296-299.

Wolff, “The Un-Curious Incident of the Baker Street Bathroom”, Baker Street Journal, Vol. 17 (March 1967): 37 – 41.