Laudanum was a widely used medicine in the Victoria Era which contained opium and alcohol and was very addictive. The terms laudanum and tincture of opium are generally interchangeable. Laudanum is mentioned once in the Canon in The Man With The Twisted Lip:

Isa Whitney, brother of the late Elias Whitney, D.D., Principal of the Theological College of St. George’s, was much addicted to opium. The habit grew upon him, as I understand, from some foolish freak when he was at college; for having read De Quincey’s description of his dreams and sensations, he had drenched his tobacco with laudanum in an attempt to produce the same effects. He found, as so many more have done, that the practice is easier to attain than to get rid of, and for many years he continued to be a slave to the drug, an object of mingled horror and pity to his friends and relatives. I can see him now, with yellow, pasty face, drooping lids, and pin-point pupils, all huddled in a chair, the wreck and ruin of a noble man.

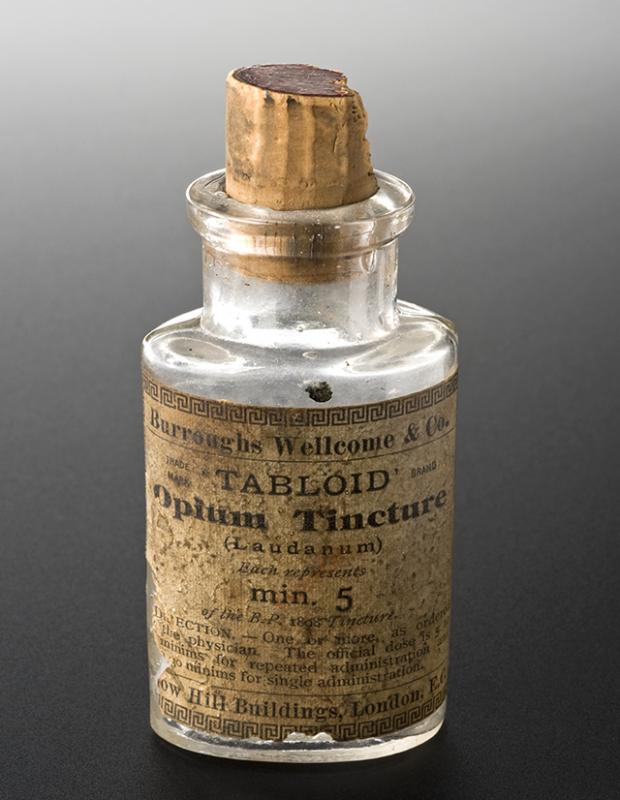

Laudanum was reddish-brown tincture that was extremely bitter. It contained almost all of the opium alkaloids, including morphine and codeine. Although there was no single formulation for laudanum, it typically contained approximately 10% opium combined with up to 50% alcohol. It was extremely addictive. Laudanum addicts would enjoy highs of euphoria followed by deep lows of depression, along with slurred speech and restlessness. Withdrawal symptoms included aches and cramps, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

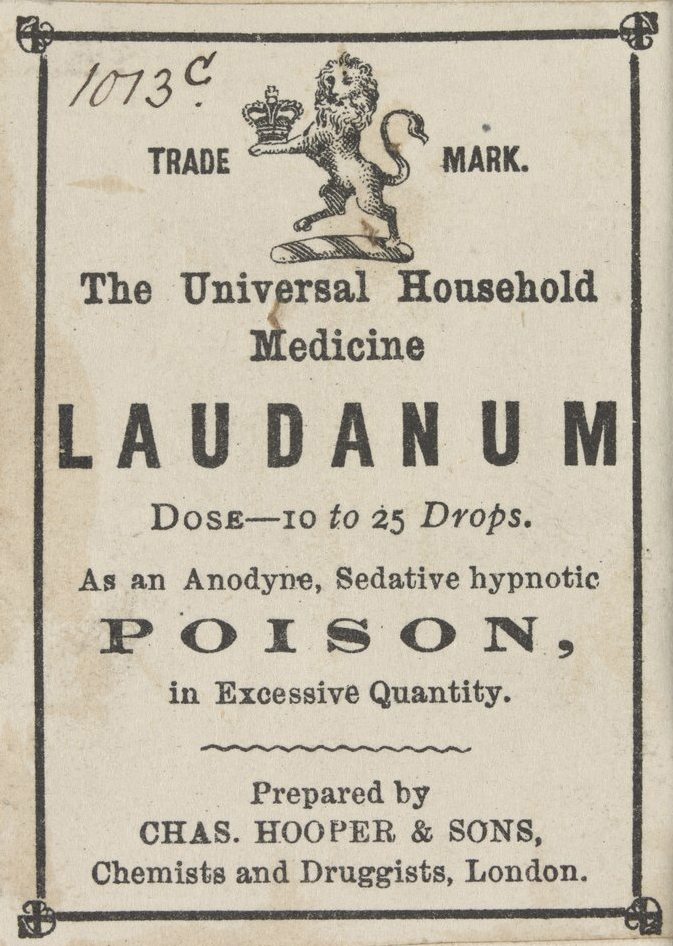

Due to its bitter taste, Laudanum was mixed with wine, whiskey, brandy, spices (usually cinnamon or saffron), honey, ether or chloroform, and even mercury or hashish. Depending on the strength of the tincture and the severity of symptoms, a typical adult dose ranged from ten to thirty drops.

Laudanum was used to treat pain, coughs, diarrhea and to induce sleep. Opiates have a wide variety affects including:

- Pain relief by reducing the perception of pain, decreasing the reaction to pain and increasing pain tolerance.

- Slowing breathing, which can help relieve chronic lung disease or anxiety.

- Slowing gastrointestinal motility, which explains why a common side effect of opiate use is constipation. For people with diarrhea, opiates was one of the few effective treatments.

- Suppressing cough reflex.

- Causing drowsiness, which laudanum became popular as a sleeping aid.

The limited pharmacopoeia of the late Victorian era meant that opium derivatives were among the most effective of available treatments, so laudanum was widely used to treat ailments from colds to meningitis to cardiac diseases, in both adults and children.

Victorian women were prescribed the drug for relief of menstrual cramps and vague aches. Many of the opium-based preparations were targeted at women. Marketed as ‘women’s friends’, these were widely prescribed by doctors for problems with menstruation and childbirth, and even for fashionable female maladies of the day such as ‘the vapours’, which included hysteria, depression and fainting fits.

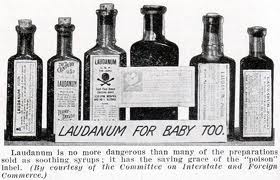

Children were also given opiates. To keep them quiet, children were often spoon fed Godfrey’s Cordial (also called Mother’s Friend), consisting of opium, water and treacle and recommended for colic, hiccups and coughs. Overuse of this dangerous concoction is known to have resulted in the severe illness or death of many infants and children.

The Victorian eras were marked by the widespread use of laudanum in Europe and the United States and also by addiction. Mary Todd Lincoln, for example, the wife of President Abraham Lincoln, was a laudanum addict. Many writers, poets, and artists (along with many ordinary people) became addicted. Bram Stoker, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and many others were all known to have used laudanum. Some managed to take it briefly while ill, but others became hopelessly dependent. Most famously, the English writer Thomas De Quincey wrote a whole book—Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821)—on his use of opium and its derivatives. The book proposed that, unlike alcohol, opium improved the creative powers, an opinion that only served to make the drug more appealing to those searching for artistic and literary inspiration.

The poet Coleridge suffered from poor health and he used laudanum as both a painkiller and a sedative. Coleridge famously admitted that he had composed Kubla Khan after waking from an opium-induced reverie. But the drug soon became an addiction for Coleridge and he began to suffer the classic symptoms of opium addiction. In a letter to a friend, Coleridge admitted it was not just the physical effects of the drug that grieved him, but its effects on his character: “I have in this one dirty business of Laudanum an hundred times deceived, tricked, nay, actually & consciously LIED. – And yet all these vices are so opposite to my nature, that but for the free-agency-annihilating Poison, I verily believe that I should have suffered myself to be cut in pieces rather than have committed any one of them.”

After the 1868 Pharmacy Act, laudanum could only be sold by registered chemists in England, who had to record who purchased the medicine, and the drug had to be labeled as a poison. But, chemists were not required to limit sales or report suspected abuse. Forty eight years later, fears about cocaine use among soldiers during World War I, especially those on leave in London, caused the Army Council in 1916 to issue an order prohibiting the gift or sale of cocaine and other drugs to soldiers, except on prescription. This was the first time that a doctor’s prescription was required by law for the purchase of specified drugs. When cocaine dealers found ways of circumventing the order, pressure from the press, anti-opium interests, the police and the army resulted in the introduction of the Defense of the Realm Act (DORA) regulation 40B in the same year. The regulation made it an offence for anyone except physicians, pharmacists and vets to be in possession of, to sell or give cocaine. The drug and its preparations could only be supplied on prescription. In 1920, Britain was obliged to introduce the first Dangerous Drugs Act to meet the 1912 International Opium Convention at The Hague’s requirements, while also incorporating the DORA 40B restrictions. The Dangerous Drugs Act laid the foundation of further legislation and control policy in Britain and consolidated the precedence of the Home Office over the Ministry of Health in the area of drug policy. The 1923 Dangerous Drugs and Poisons Act, imposed stricter controls on doctors and pharmacists with respect to dangerous drugs, introduced more severe penalties and higher fines and sentences, and expanded the search powers of the police.