Every reader of Sherlock Holmes forms in his or her imagination an image of the sitting room at 221B, where almost every story begins. The Canon provides many details of what was in the rooms rented by Holmes and Watson, but relatively few clues about the design or layout of the building at 221B Baker Street. This article reviews previous suggestions for the architectural design of 221B and explains why they simply to not conform with architectural reality or the clues provided by Dr. Watson in his writings.

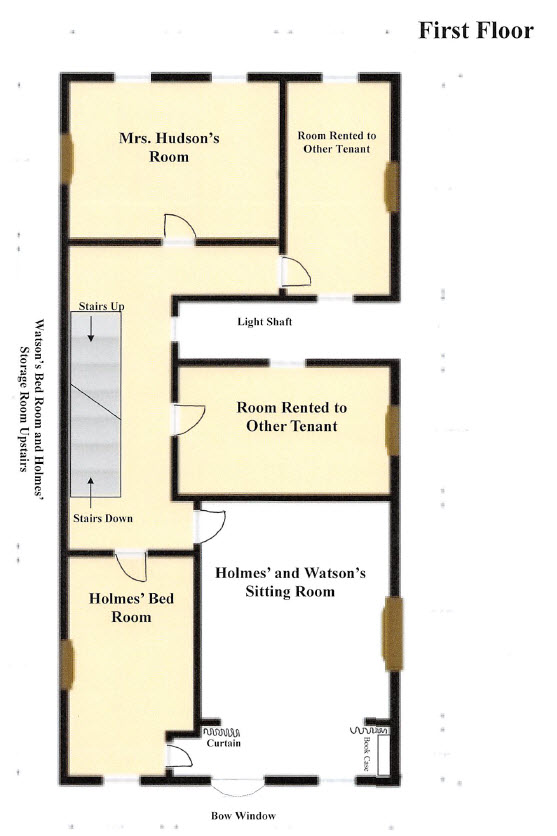

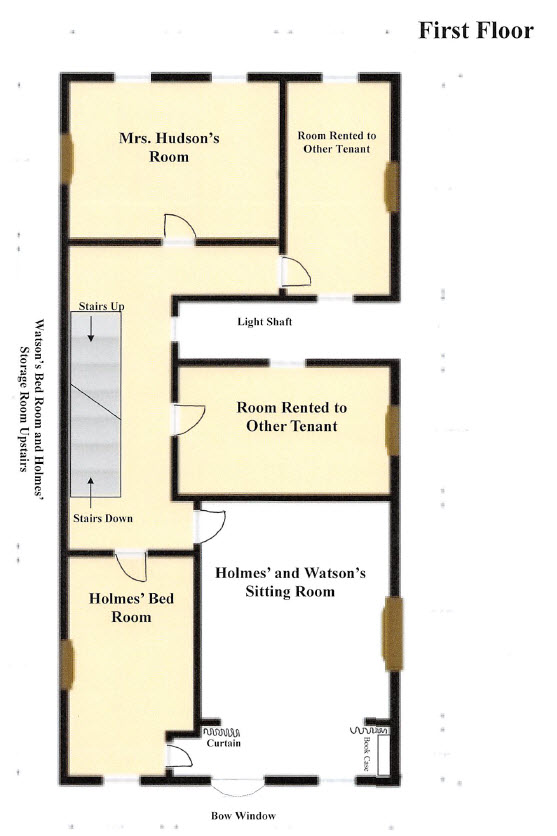

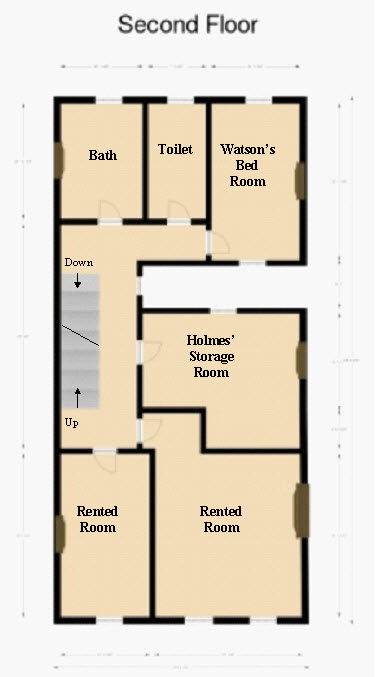

I suggest this possible lay out of the First Floor of 221B based on what is known about the terraced houses in Marylebone in the 1880’s and the information to be gleaned or deduced from the Canon. (Note to Americans: our first floor is the ground floor in London and our second floor is what the British call the “first floor.”)

These are the primary clues we can derive from Watson’s reminiscences:

- Dr. Watson in A Study in Scarlet described a, “single large airy sitting-room, cheerfully furnished, and illuminated by two broad windows.”

- The door to Holmes’ bedroom is at the top of the stairs and stairs lead down to street level. Study in Scarlet.

- There are seventeen steps on the way up to the sitting room. Scandal in Bohemia. Sign of Four.

- Holmes’ bedroom is once suggested as being upstairs of the sitting room, Adventure of the Beryl Coronet, but in more stories it is connected to, or at least next to, the sitting room, Adventure of the Mazarin Stone. “With a nod he vanished into the bedroom.” A Scandal in Bohemia. “He sprang to his feet and passed into his bedroom.” The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton. In The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet, Watson writes that Holmes “hurried to his chamber and was down in a few minutes.” In other stories, Watson refers to Holmes’ “bedroom.” A Scandal in Bohemia and The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton. Perhaps the use of “chamber” simply referred to another room used by Holmes upstairs, either to store his papers or perhaps contain his many disguises. Two stories mention a room upstairs used to store Holmes’ large collection of papers. Adventure of the Six Napoleons and Musgrave Ritual.

- In The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone, Holmes’ bedroom is connected to the sitting room by a second door (in addition to the door at the head of the stairs).

- Holmes’ bedroom has a fireplace. The Adventure of the Dying Detective.

- Watson’s bedroom is upstairs of the sitting room. Sign of Four, Five Orange Pips, Adventure of the Speckled Band, Adventure of the Beryl Coronet, Problem of Thor Bridge

- Watson’s bedroom faces the rear of the house from which he can see a lone tree. Problem of Thor Bridge. Watson’s bedroom had a mantle and hence a fireplace. The Adventure of the Speckled Band.

- There was at one time a waiting room downstairs of the sitting room. Adventure of the Mazarin Stone.

- The sitting room had a fireplace with a mantle (as described in many, many stories) and to the right of the fireplace was a book shelf. Adventure of the Noble Bachelor, Adventure of the Sussex Vampire.

- At least one window in the sitting room is tall enough for Watson to stand in and for Holmes to look over Watson’s shoulder at the street below. Adventure of the Beryl Coronet.

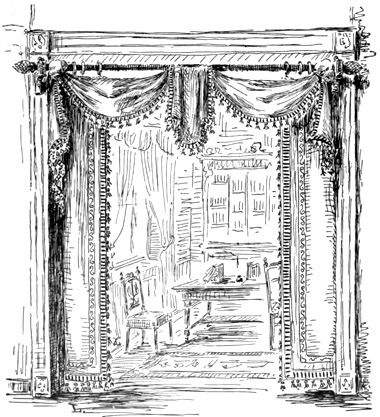

- Two stories mention a “bow” window in the sitting room. Adventure of the Beryl Coronet and Adventure of the Mazarin Stone.

- Watson describes in The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone how the page, Billy, “drew away the drapery which screened the alcove of the bow window.” That alcove was big enough to hold a chair containing a mannequin that looked like Holmes.

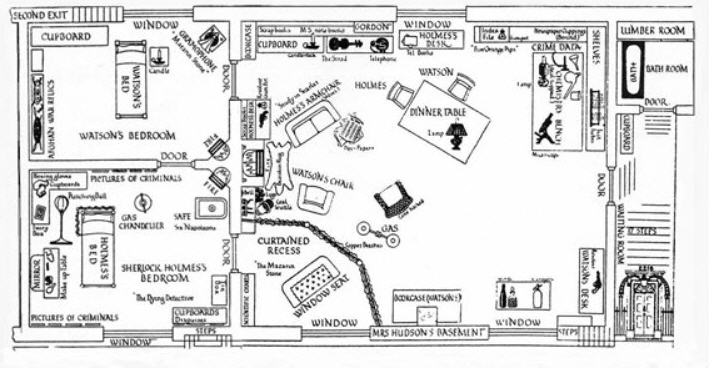

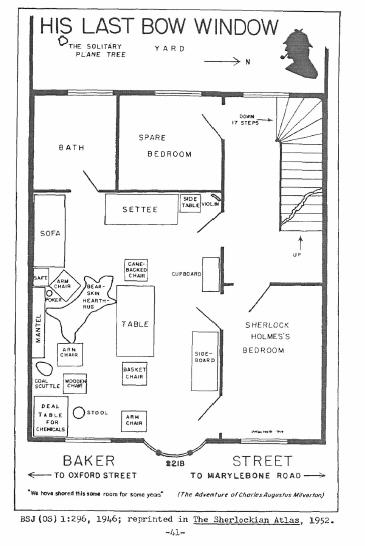

There have been attempts through the years to illustrate the design of 221B. For example, Ernest Short made this drawing around 1948 and it was published in The Strand in 1950:

This diagram tries to show the contents of the various rooms, but it is woefully inadequate for several reasons, including:

- There is no bow window

- Watson’s bedroom is on the same floor as the sitting room and connected to Holmes’ bedroom.

- The room shown has windows on both sides. A terraced house in Marylebone at the time would have been narrow and deep and not so small that it was just one room deep.

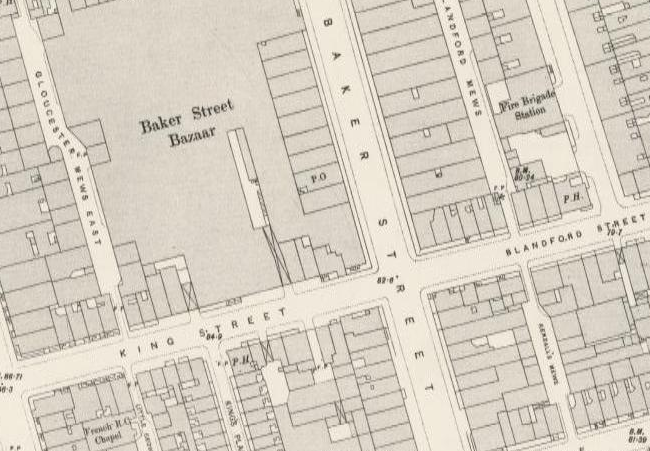

The terraced houses of Marylebone were shaped like thin rectangles on the ground floor and would not have been so short that the sitting room would have had windows facing the rear of 221B. Before electricity, many houses had light shafts in the middle so that interior rooms could have windows and thus light during the day. Almost every room had a fireplace for heat.

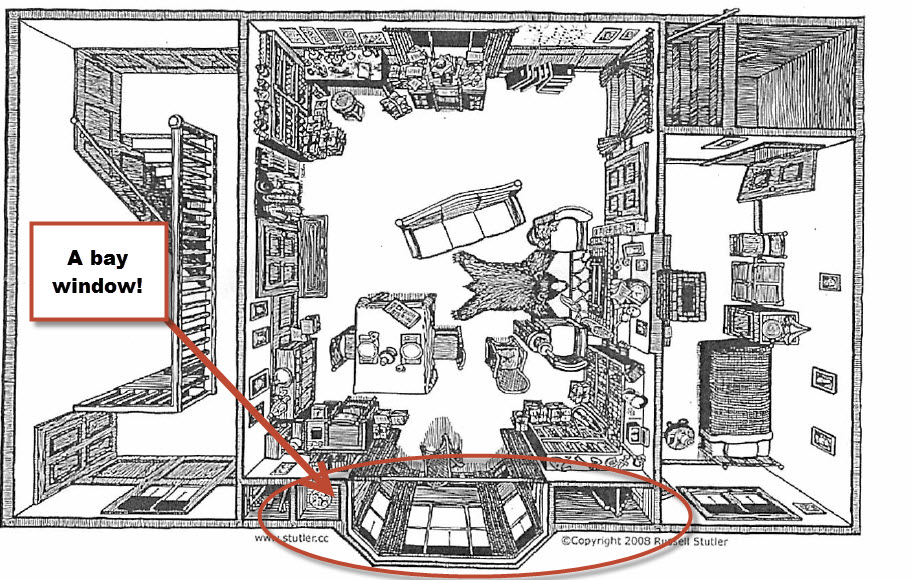

A diagram of the First Floor of 221b drawn in 2008 by Russell Stutler is commonly found on the Internet.

This diagram also depicts the First Floor of 221B as just one room deep and no house on Baker Street or nearby streets in Marylebone were so constructed. The terraced houses (which did not have terraces and were what we would now call row townhouses sharing common walls) were narrow and deep and usually three or four stories tall. This diagram has Holmes’ bedroom opening onto a second and ridiculously steep stairway. More fundamentally, this diagram depicts a bay window, not a bow window.

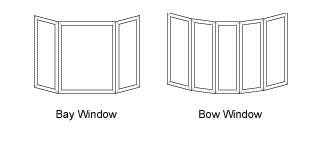

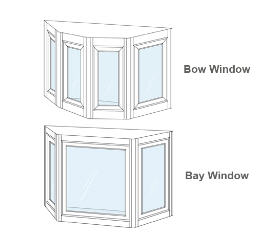

A bay window has three openings, consisting of a larger, central picture window with two other windows, usually smaller, on either side that are almost always angled back A bow window usually has four or five windows (or more) and its structure is curved, creating a rounded appearance on the outside of the home. A bow window can be placed into a wide window frame flush with the wall.

A suggested diagram of 221B was put forth in 1946 by Julian Wolff.

Wolff’s layout is more plausible, but it still shows a building that is too square and not deep enough to be the First Floor of a terraced house in Marylebone, especially on Baker Street. Three doors on Holmes’ bedroom makes little sense and that unusual layout leaves almost no space for the items described in his room. The Canon does not directly mention a separate room with a bath tub. In The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax, Holmes deduces that Watson has enjoyed the Turkish baths and asks him,“Why the relaxing and expensive Turkish rather than the invigorating home-made article?” In The Sign of the Four, Watson returns to Baker Street after a long day of sleuthing and Watson was,“limp and weary, befogged in mind and fatigued in body.” But then Watson writes,”[a] bath at Baker Street and a complete change freshened me up wonderfully. When I came down to our room I found the breakfast laid and Holmes pouring out the coffee.” This passage implies that Watson’s bedroom and some place where he could bathe were upstairs from the sitting room.

If a separate room was set aside at 221 Baker Street for a bath in the 1880’s, it would have been shared by all of the tenants, Mrs. Hudson and probably her employees. The bath room shown in Wolff’s floor plan would have been for Holmes and Watson only and could not have been easily accessed by other tenants.

In fairness to Short, Stutler and Wolff and their diagrams of 221B, they were focused mainly on where furniture and various items were in the sitting room and not on architectural design. I do not quibble with their placement of the bear skin rug, for example, but I am skeptical of their layout of the building itself.

I humbly suggest that this design is consistent with all of the Canon’s descriptions of 221B Baker Street:

This design conforms with all of the descriptions in the Canon summarized above and even meets the challenge of the description in The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone.

This would be a “First Rate Terraced House” of the sort built in the Portman Estate in the late 1700’s on or near Baker Street with three tall windows facing the street on the first floor (the American second floor).

Terraced houses were a row of houses of uniform height and facade divided by common walls. We would call these townhouses or row houses today. The Building Act of 1774 divided terrace houses into four classes, defined by the number of stories, ceiling heights, road widths and wall thicknesses. First rate houses faced streets and lanes, were worth over £850 per year in ground rent and occupied over 900 square feet of ground space. These houses usually had four stories, plus a basement, so they often had a total of over 4500 square feet.

The Portman Estate owned almost all of the land around Baker Street and the terraced houses were leased for 50 or 99 years in the 1800’s. The lessee’s family would occupy the entire house if wealthy or rent the house to one or more tenants. The area around the southern end of Baker Street was developed in the late 1700’s.

The ground floor of a house, such as 221 Baker Street, which was rented to multiple tenants, would typically have contained one or two businesses on the ground floor. The kitchen and laundry room would be in the basement. The landlady, Mrs. Watson, would probably have lived on the first or second floor. The cook and maid would have had smaller rooms on the top floor.

One can imagine the agent of the Portman Estate showing the rooms to Mrs. Hudson before she signed her lease and explaining the unusual curtain across the width of the sitting room as follows:

Having shown off the newly installed flushing toilet and the bath with hot water continuously piped in on the second floor, the agent lead them back down to the first floor and ushered Mrs. Hudson into the large sitting room facing the street. “The prior tenants on this floor installed this odd curtain that bisects the room because the lady suffered severe headaches that required total darkness. Her husband was able to draw these thick drapes across the room and still sit in his easy chair watching the traffic below through this handsome tall bow window while his wife eased her pains.“

“Perhaps your new tenant could use this room for seances to contact the departed or mayhap to develop photographic plates,” he tittered. If you wish to remove the curtains and these small side walls, it will be at your expense, with plans pre-approved and tradesman from the Estate’s list,” he added.

My suggested floor plan would explain why in The Study in Scarlet, Watson heard the maid then the “landlady’s stately tread” pass the sitting room door on their ways to bed. This layout allows Holmes to quickly go to his bedroom and it provides the curtained alcove of the bow window connected to Holmes’ bedroom as described in The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone.

Moreover, there were terraced houses in Marylebone in the 1880’s with this almost exact layout on the First Floor (less the odd curtain across the end the sitting room, which must be explained with some plausible back story).